A few years ago, DePaul professor Dr. Christina Rivers started teaching a different kind of law and politics course.

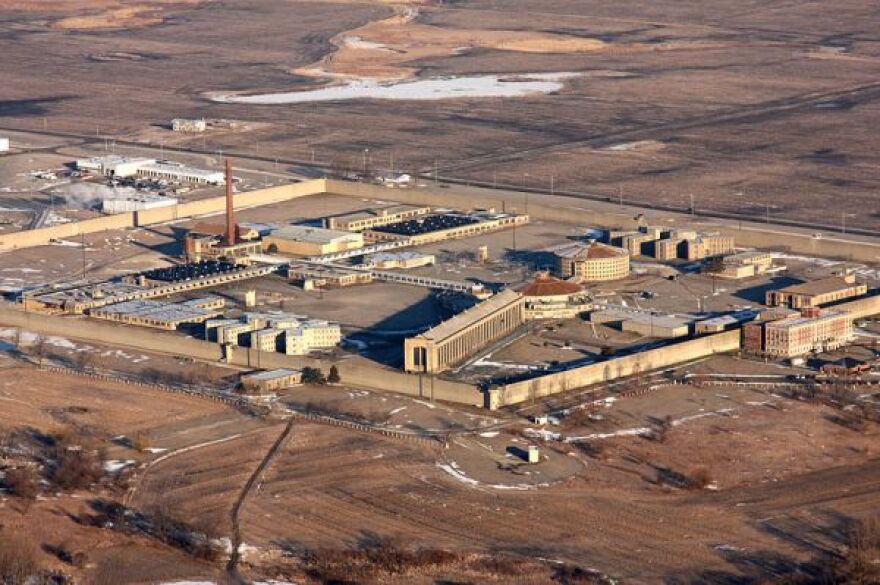

About half of the class is made up of typical DePaul students and the other students are serving time at the Stateville Correctional Center. The class is held inside the maximum security prison.

Her class does a group project where they create a policy proposal. Half of the projects students presented were about voting rights and education in the first year at Stateville.

A plan for “The Re-Entering Civics Education Act” blossomed from there in the Illinois General Assembly.

“So you have the directly impacted folks, in some cases, pretty much at the head of these efforts,” she said.

Rivers knows how many bills die in committee, so she was surprised how quickly the plan accelerated through the process.

“I was expecting them to kind of pat us on our heads and smile and say, ‘Oh, yeah, this is a good idea, we'll think about it,’ and then send us on our way,” said Rivers.

Ann Gillespie was one of the Senate co-sponsors of the proposal. For her, the most important part was that the programs are peer-led instead of just taught by a teacher or staff member.

“This is a community responsibility that we are saying, 'You now have this right to exercise and it’s important that you do it.' I think just that concept is what's the most critical aspect of it,” said Sen. Gillespie.

The classes are part of release protocols for people leaving within a year. It’s the first of its kind in any state in the country.

“I really hope they're not the last,” said Rivers. But the issue runs deeper. She says many incarcerated people don’t even know what their rights are.

“Whenever I go to register voters at Cook County Jail, so often they'll say, ‘You know, we were told that we couldn't do this,’” she said. “Yeah, and so there's profound misinformation on voter eligibility not just in Illinois, but around the country.”

That’s partially due to the array of different laws in different states around felony disenfranchisement.

In Illinois, once you’re released from prison you can re-register to vote right away. In some states, Rivers says parole, probation or court fines can cause your rights to be withheld.

“It can become all but permanent if it's relying on people paying back fees and fines where they don't have money to do that,” said Rivers.

Iowa is now the only state where people charged with felonies lose their right to vote for life. Even with Illinois’ more progressive stance, the courses emphasize your need to get an ID to facilitate your voter registration and help you get other necessary paperwork.

Timna Axel is the communications director of the Chicago Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights. They also helped craft the plan. She says education and civic engagement play a big role in reducing recidivism.

“Those folks tend to have a lot stronger bonds when they leave, and so they have a better chance of staying out of the incarceration cycle,” said Axel.

The civics education courses come at the same time as a measure to expand voting rights for pre-trial detainees who haven’t been convicted of a crime.

It allowed the Cook County Jail to become a temporary polling location during the midterm elections in March.

Alex Boutros was one of the DePaul students in the inside-out class. Now she’s an organizing manager at Chicago Votes. They’re a non-profit voting rights organization and advocacy group.

She got to go to the jail during early voting.

“It was really beautiful to know that these men are passing their ballot and really making their voice heard, even though knowing that they're going to be put in a cage when they're done,” said Boutros.

Boutros also says it mandates every county jail to have a vote-by-mail system in place.

The civics classes will look a little different for people in youth facilities.

Heidi Mueller is the director of the Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice. They hope the courses can be co-lead by peer leaders and professional education trainers. She says they might also have to get staff trained in order to carry out the classes.

Advocates hope it can lead to expanding the limited higher-ed offerings in correctional facilities.

Timna Axel with the Chicago Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights says it’s good these laws were partially written by people who are in prison themselves. That way there’s investment from the people affected to keep fighting for their rights when they get out.

“The more seriously we all take this responsibility to be civically engaged and to vote, the more likely we are to keep these very cherished rights that we have,” said Axel.

The general elections are in November. The law mandated courses begin by the end of June. But the program relies on outside education instructors. And with two people at Stateville dying of COVID-19 and others contracting the virus, it will be more than likely delayed.