More than 1 in 5 students in Illinois were chronically truant last year. That means they missed over 5% of the year without a valid excuse.

It’s illegal for Illinois school districts to refer students to local law enforcement to be punished with a fine for truancy. The law changed back in 2019.

But not every school stopped. Last year, an investigation from ProPublica and the Chicago Tribune found Illinois schools have still issued over 1,000 truancy tickets since.

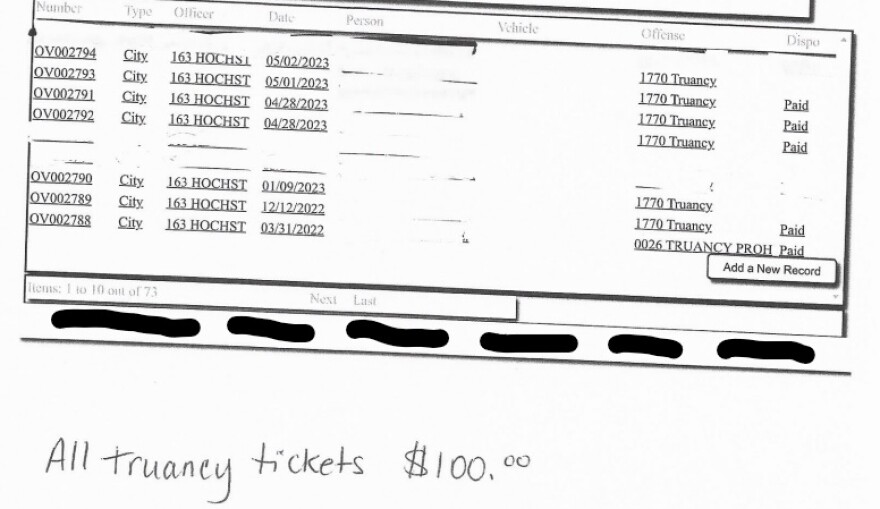

In a few northern Illinois districts, police have issued dozens of truancy tickets worth hundreds of dollars. In Mendota, students have paid $100 truancy tickets as recently as this May -- nearly four and a half years after the state prohibited the practice. According to public records obtained by WNIJ, Mendota police have written students 45 truancy tickets since 2019.

Denise Aughenbaugh is the superintendent at the Mendota Township High School District.

“I agree with the full intent of it," said the superintendent, "that it is not in the best interest of a student to have additional fines and fees laid upon them, especially from a school district."

She says because they have a school resource officer working in the building, they’re not technically referring students to law enforcement. Aughenbaugh says their resource officer is part of their truancy review meetings and might issue tickets on their own, but she says they’re making a concerted effort to stop.

This past school year, fewer than 10 were issued and she hopes to make it zero this year.

Police in Streator issued 25 truancy tickets in the 2021-22 school year but cut it to zero last year.

Beau Doty is the assistant principal at Streator Township High School.

Despite the fines, he says the truancy system has become much less punitive.

“When I first started in this position," said Doty, "you had judges that would actually put kids in detention home because of truancy."

Now, school districts are required to exhaust as many interventions as possible to help truant students before there’s any punitive action like a suspension, expulsion or court referral.

In Streator, they’ve hired a full-time truancy mentor to help facilitate those interventions. Her name is Sarah Price.

Every day, she scans attendance reports to see who made it to school. Once a student reaches a certain number of absences, her role comes into play. She sends letters home and visits families. She says they have weekly truancy intervention groups to try to get students back on track academically.

“I always relate it to kind of a big brother, big sister kind of thing. Like, ‘I'm here for you, let's do this!’," said Price. "They’ll try to get them to do a club or, they'll even help them with their homework."

She says they want them to feel connected with their peers and teachers and want to come to school -- and clubs and activities can help with that. The school gives out prizes for students who miss fewer than two days a month.

For those who fall far behind because of truancy, the school has an alternative program housed inside the high school. It’s a separate classroom, with their own teacher who helps guide them through online credit recovery. She says it has to be online because students are all at different levels. Some might be seniors who are at junior status because of credits or juniors at freshmen status.

“I want to say 10 or 12 kids graduated last year," she said, "that probably wouldn't have graduated if they weren't in our program."

Samantha Halm is the director of student services for Regional Office of Education 35, covering 29 school districts across LaSalle, Marshall and Putnam counties. Part of their work involves truancy, and Halm started at the regional office as a truancy officer. She says they act as a mediator between school districts and families.

“School districts will make a referral to our office," she said. "We have the discretion to either take the referral or kick it back and say this doesn't meet criteria for truancy."

Last year, Halm officially served 120 truant students on her own. She started her days stopping at houses, and waiting with kids at their bus stop to make sure they get to school.

“We reach out to families to try to get to the bottom of what that issue is,” she said. “Is it a mental health challenge? Is it bullying? Is it poverty? A lot of the families that are referred for truancy live at or below the poverty line.”

They can request parent-teacher conferences, refer out to school social workers or the Youth Services Bureau for counseling. Halm and Price both say that there’s a youth mental health crisis. Halm just got trained in Youth Mental Health First Aid to better help students in crisis.

The regional office also drops off gas cards for families experiencing transportation challenges that can cause truancy. Halm says it’s been a major shift to discourage schools from sending students to get fined or referred to the State's Attorney's Office to juvenile court.

“Punishment doesn't work," said Halm, "and we need to find some practical solutions and do what we can to help as much as possible."

The youth mental health crisis and academic struggles stemming from the pandemic aren’t going away any time soon. But Halm says there’s plenty that school districts can do to help truant students and their families. They can show students the cost of missing out on school and not just the cost of a fine.