Treatment is one piece of the puzzle in tackling the opioid epidemic. But people seeking help in Illinois may face another major challenge … paying for it. Health insurance companies pose different requirements for getting these medications. Some physicians say this can lead patients back to the streets. In this week’s Friday Forum, WNIJ’s Jessie Schlacks looks at obstacles for people ready to defeat their addiction ... and how lawmakers are trying to fill the gaps.

Dennis Brightwell, a medical director with Rosecrance, says that – as a practicing physician – he’s on the front lines dealing with insurance companies and opioid treatment.

Brightwell says private insurance restrictions sometimes can be the biggest obstacle between a patient and recovery. He says he’s trying to help a current patient get treatment through her insurance plan.

“She wanted to get on Suboxone because she was really struggling with her opiate addiction, which in her case was pills,” Brightwell said, “and she knew it. She says, ‘If I have two pills, I will take them. If I have ten, I will take them. I don’t have any control over this. I need to get some help for this.’”

But Brightwell says the patient’s private health insurer blocked the prescription at the pharmacy for “prior authorization,” which means the prescriber must submit a patient-history form. He says the insurance company reviews the information to decide whether the physician is “doing the right thing.” Brightwell says it causes a delay.

“She’s anxious about it and worried. I don’t have another option for her,” he said, “if the weekend comes and we can’t get it for her and she can’t buy it.”

He says these delays – which can last days – can lead to losing patients.

“We really only have one other option for suppressing your withdrawal symptoms – and that’s to go out and use again,” Brightwell said, “and then they don’t come back the next day because we’ve lost that opportunity. And that happens.”

Brightwell says private insurance companies shouldn’t be making the ethical calls.

“All these little pieces of data that they’re saying, ‘You need to do this. You need to do this. You should do this. You can use Buprenorphine to start, but you have to switch,’” he said, “that is like micro-management that is completely crazy. It doesn’t make any sense.”

And, he says, it boils down to how much treatment costs the insurer. “The more expensive treatments are more likely to get prior authorization than inexpensive treatments,” he said, “and this is moderately expensive.”

Brightwell says some commercial insurers may refuse coverage if a patient is sober for more than three days. He says some people will fail drug tests intentionally so they can get their treatment.

“And that is crazy that we’re trying to teach patients to play those games to get the help they need,” he said. “So that could be fixed legislatively, too – to write a standard that covered non-medication – the rest of the treatment, which is absolutely critical.”

Brightwell says he wishes all his patients had Medicaid insurance, because a 2012 amendment requires Medicaid to cover substance-use treatment fully without prior authorization. Brightwell says this makes the process much easier.

“And that has been a huge help, because an awful lot of patients I take care of here are not wealthy,” he said, “so, their primary insurance is Medicaid.”

Brightwell says he recently sent a plea to Illinois Lieut. Gov. Evelyn Sanguinetti to regulate private insurance the same way as Medicaid. Sanguinetti is co-chair of the state’s opioid prevention and intervention task force.

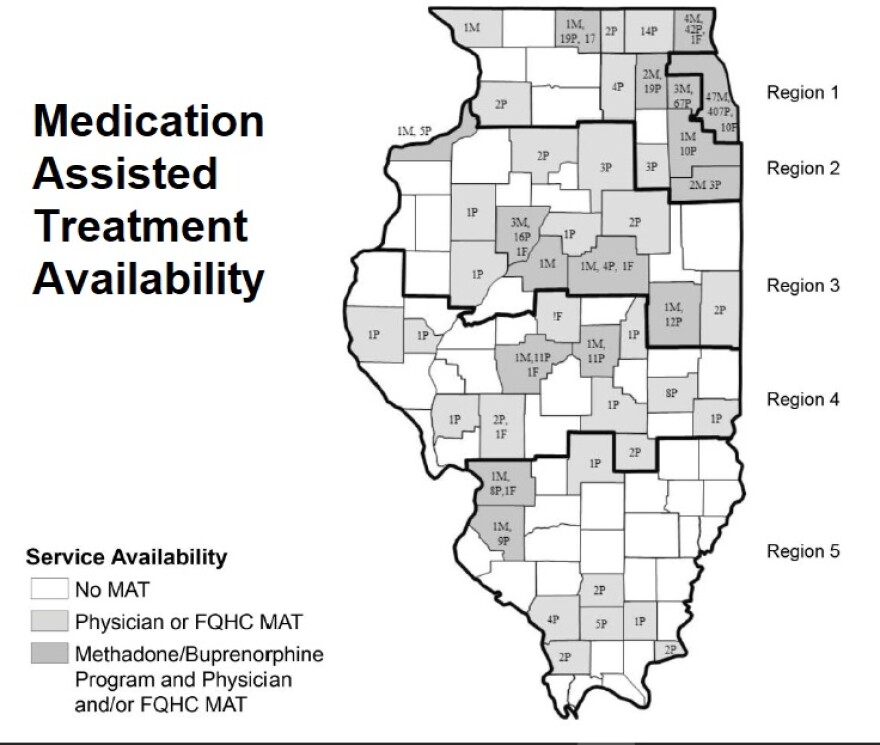

In an email statement to WNIJ, Sanguinetti says Illinois is attacking the opioid overdose epidemic head-on. The State of Illinois Opioid Action Plan, issued in September 2017, details the task force's analysis of the epidemic within Illinois and its proposal to reduce its impact. Sanguinetti says her group is “utilizing federal dollars to pilot hub-and-spoke projects in geographic areas of the state lacking access to Medication-Assisted Treatment.”

Sanguinetti says the hub-and-spoke model is recognized as an "evidence-based regional approach" for delivering Medication-Assisted Treatment. It involves designated treatment centers to give medication and community resources to provide additional support.

She says they “plan to request bids for these projects next month and have them operating this summer.”

Meanwhile, other lawmakers are keeping the treatment access discussion going on a national level. U.S. Rep. Bill Foster, D-Naperville, has made the opioid crisis a pinnacle issue. He says he’s glad Illinois is working to boost availability of Medication-Assisted Treatment.

“There are real problems in rural areas where there may not be a clinic within a reasonable drive,” Foster said, “and so, I have a lot of sympathy for trying to have some special dispensation there.”

He says insurance companies often refuse to cover treatment or work hard to get doctors to do what’s cheap -- which he says is to prescribe opioids instead of physical therapy or more specialized drugs.

“Medical treatments for patients suffering from addiction is much more expensive than a medically assisted product that will keep them out of a recovery center,” Foster said, “and, more importantly, lead them to live productive lives.”

Foster says he wants to make medically assisted treatment affordable for anyone who has insurance – including private insurance.

“It’s one of the things that we’re working to get the rules changed,” he said, “because this is really an all-hands-on-deck situation, and we can’t be excluding competent providers.”

Foster says he’s pushing for the extra federal money allocated for the opioid crisis to be invested in high quality programs. But he says there should be more follow-up with patients to see what’s working long-term. He says Congress is making progress – but still has a lot of work ahead.

Until effective treatment becomes affordable for all who need it, a resolution to the opioid addiction crisis is likely to remain elusive.