Roughly one million Illinoisans gained insurance care through the Affordable Care Act. That's had an impact on the way health care is delivered throughout the state.

Nine years ago, Kris Hayden was undergoing cancer treatment and she felt guilty.

She followed the treatment regimen prescribed by her doctors, received two stem-cell transplants, and improved. But there was an unanticipated price: Health insurance rates more than doubled for employees of the small office supply company that she ran with her brother in South Elgin. Individuals who had been paying about $250 a month saw their rates increase to around $600.

“I felt bad about people having to spend more money because of me,” Hayden said. "I felt like we were being punished."

Eventually, the company dropped its private health coverage and employees used the Affordable Care Act to buy insurance through the Illinois health-insurance marketplace. “It was better insurance and less money at that time,” said Hayden, 49, who is now in remission. “It solved a lot of issues for us as a small company.”

Hayden is one of 350,000 Illinoisans to access individual health insurance coverage through the state’s marketplace since Obamacare was enacted. Another 640,000 receive coverage through a federally funded expansion to Illinois’ Medicaid program. The percentage of uninsured people in the state has been cut in half to 7.7 percent.

“Generally speaking, the ACA has worked really well in Illinois. We’re at historic levels of coverage,” said Alicia Siani, a manager at EverThrive Illinois, a patient advocacy group. Record numbers of people nationally have insurance as well, with 11.3 percent of adults uninsured today compared to 18 percent in 2013.

While that is good news, public opinion on the Affordable Care Act is divided in Illinois just as it is nationally. About half of the people surveyed favor the act, and the other half would like to see change.

Premium and deductible costs in Illinois have skyrocketed, leaving some unable to afford the out-of-pocket costs to access their health care. U.S. Rep. Peter Roskam, R-Wheaton, lists hardship cases on his website. They include:

- A St. Charles family’s insurance plan increased from $300 to $1,100 a month for a bronze plan, which is supposed to have low premium costs and high deductibles.

- Another constituent in Barrington saw his premiums grow by 40 percent, while he lost access to the nearest hospital and half of his providers.

- The premiums for a Lisle man went up 75 percent in 2016 and another 41 percent this year.

As President Donald Trump works to make good on his promise to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act, there is no question some changes will occur. What’s unclear is what will change and how those changes will impact Illinois.

Proposals including the American Health Care Act have Siani and other health-care advocates and providers in Illinois worried. They are concerned that coverage for people like Hayden will be compromised and that there will be a ripple effect negatively impacting health care, hospitals and even the Illinois budget and economy.

Those in favor of change, like U.S. Rep. Rodney Davis, R-Taylorville, think too many people are underinsured and that too many insurance companies are leaving the market, reducing competition and contributing to higher costs. Just this year, the state’s health insurance exchanges saw average increases of 40 to 50 percent for their health insurance plans, according to the Illinois Department of Insurance.

Some people qualify for discounts based on income, but many struggle to pay for the insurance premiums and deductibles to access their health care. Davis says a family of four in his hometown might pay $13,000 for a health insurance premium and then have a $6,000 per person deductible.

“That’s unaffordable, catastrophic-only insurance,” he said. “That’s what we have to address.”

Davis would like to see fewer people using Medicaid and more having access to affordable individual plans or employer-based plans. Davis, whose wife is a cancer survivor, also wants those with pre-existing conditions to have coverage.

It seems everyone, from advocacy groups to the public to politicians, wants to see more Americans have health insurance and access to good, affordable health care. But how to achieve that goal is another matter. Democrats in Washington, D.C., staunchly stand behind the ACA, while Republicans struggle to find consensus on issues like mandatory coverage for pre-existing conditions. “Stay tuned. This thing moves around by the day,” said Paul Keckley, a national health-care industry expert.

Change is coming.

The Trump administration and Republicans have a three-part strategy to repeal and replace the ACA.

The first is a sure thing: Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price can make administrative changes to health care by rewriting regulations and rules.

The other two parts— one, a legislative overhaul to repeal and replace Obamacare; and the second, an effort to tackle issues like capping medical malpractice damages — are more difficult because they require legislation agreed on by a majority of Congress.

Congressional Republicans have been scrambling through March and April to overhaul the ACA using a Senate parliamentary rule called budget reconciliation. They can use a fast-track budget bill that only requires a simple majority of 51 rather than the usual 60 needed to pass a bill through the Senate.

Their first attempt at that bill — the American Health Care Act — failed to be called for a vote in March because it lacked support. Different groups of Republicans have been meeting since then to reach consensus and are considering many issues like Medicaid funding, tax credits, coverage for pre-existing conditions, and what kinds of health-care benefits should have required coverage.

From news about the discussions, nothing appears to be sacred. One proposal from the conservative Freedom Caucus called for doing away with some “essential health benefits” that are guaranteed by the ACA. One argument is that people shouldn’t have to pay for coverage like maternity care or substance abuse treatment if they are never going to use it. Meanwhile, another proposal would allow states to opt out of regulations requiring coverage for pre-existing conditions because of the concern that those conditions drive up premium costs for everyone.

In Illinois, proponents of Obamacare worry a repeal or changes to the act will have dire repercussions across the state. The roughly one million Illinoisans to gain insurance care through the ACA have had an impact on the way healthcare is delivered in the state. Rather than stabilizing patients in emergency rooms, more providers are able to ensure patients get the right care at the right time, which improves patient outcomes and lowers costs, says A.J. Wilhelmi, president and CEO of the Illinois Health and Hospital Association.

Dave Ranlett’s story is a good example of that. A former chef who lives in Park Forest, Ranlett lost his job several years ago because he was unable to stay on his feet for long hours. Morbidly obese, he faced the real possibility of developing diabetes and other expensive, chronic conditions.

With the loss of his job, Ranlett also lost his health insurance; but, under the ACA, he was able to get Medicaid. Ranlett qualified for bariatric surgery and now is working to re-enter the workforce. He sees Medicaid as a stopgap measure. “Some people will say to stop eating, but it doesn’t work like that when you’ve got 240 pounds to lose. That’s a 6’4” bouncer. I needed to ask for help,” Ranlett said.

There’s more to his story: Ranlett received care through the Cook County Health & Hospitals System. Because more patients like Ranlett have insurance, the system has been able to reduce its dependency on tax support by 75 percent -- or about $370 million -- over the last eight years, Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle has reported. That is a national trend.

By increasing health insurance coverage for millions of Americans, the ACA also has improved the finances of hospitals and health-care providers across the country. In the past, costs incurred by patients who couldn’t pay were absorbed by the provider. “There’s an offset that is pretty clear,” said Keckley, who has written widely about healthcare and worked as a facilitator in Washington. “If you look at it objectively, in those states where Medicaid expansion has occurred, you’ve seen bad debt in hospitals go down.”

Many hospitals and health-care providers in Illinois have seen their budgets boosted because of coverage for patients. “What’s at stake is the health and well-being of hundreds of thousands of people in Illinois,” Wilhelmi said. “Hospitals don’t turn patients away. When they see the uninsured, they must still pay for those patients.”

With 40 percent of the state’s hospitals operating in the red or at very thin margins, any disruption to the payment structure could seriously harm the Illinois health-care system and, in turn, the state’s economy, Wilhelmi says. Jobs in health care would be cut, as would services.

Another consequence involves patients. If patients lose their insurance, they will lose their ability to develop relationships with primary-care doctors and specialists, says Larry McCulley, president and CEO of the Southern Illinois Healthcare Foundation. “For us, it is about how individuals are impacted,” he said. Any drop in Medicaid coverage in the state would affect rural Illinois the worst. Already there are shortages of physicians in those areas, making access to care challenging.

The other 30 states that expanded their Medicaid programs face similar difficulty, but Illinois would deal with the greatest hardship. Here’s the back story. Federal payment rates for Medicaid were set in 1965 when Illinois was wealthier. Today, Illinois receives less federal funds per Medicaid beneficiary than any other state in the country.

One proposal out of Washington, D.C. calls for a per capita cap on federal Medicaid spending per beneficiary. Illinois would be locked into its 2016 Medicaid expenditures, leaving the state in last place for Medicaid spending.

“That could have been a catastrophe for the state of Illinois,” McCulley said. “Our ability to provide the same level of coverage and care and access would be hampered without a comparable replacement.”

Consider the disparity: Even though Ohio has a smaller population and fewer Medicaid patients than Illinois, it received $4.6 billion more in Medicaid funding than Illinois in 2015.

Likewise, experts say Illinois stood to lose $40 billion in federal money over the next 10 years if the American Health Care Act had been approved. The dollar loss was based on a report put out by the Congressional Budget Office that said 24 million Americans would lose coverage under the plan. “Illinois can’t withstand billions in Medicaid funding cuts to patients, health care delivery systems, hospitals, the state economy and budget,” Wilhelmi said.

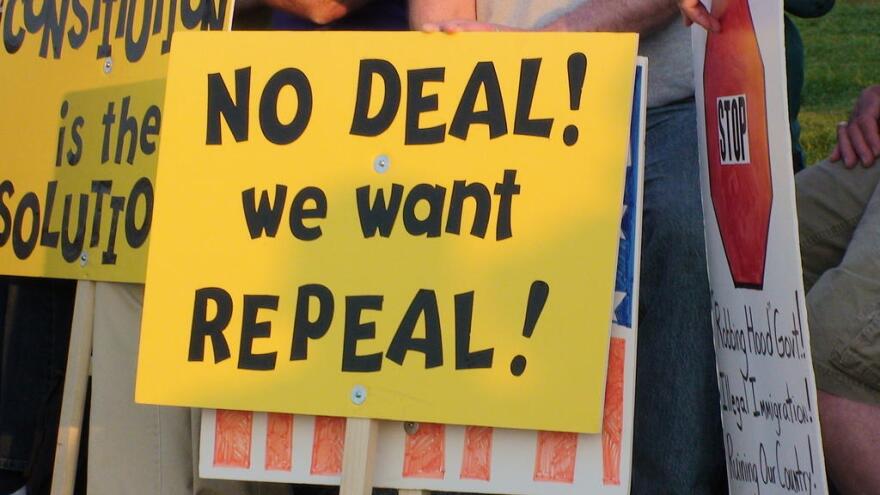

Supporters of Obamacare rally against its repeal in Washington, D.C. in February.

Supporters of Obamacare rally against its repeal in Washington, D.C. in February.

Credit Ted Eytan / Flickr

Illinois Democratic members of Congress have been staunchly against any proposed changes to the ACA. “Unfortunately, this replacement would have made our healthcare system significantly worse, harming tens of millions of Americans, including some of our most vulnerable,” said a statement by Dan Lipinski, who serves the Illinois 3rd District on the southwest side of Chicago. He is one of a few House Democrats still in office after voting against Obamacare in 2010 and would support changes if they rein in costs and expand coverage without diminishing care — a tall order.

U.S. Rep. Jan Schakowsky, D-Evanston, called Republican efforts to repeal and replace the ACA a spectacular failure. “Republicans today have demonstrated their complete inability to govern,” her statement read. Democrats plan to use that line of criticism as they target Congressional seats in the next election. U.S. Rep. Peter Roskam holds one of those seats in the 6th Illinois Congressional District.

Many Illinois Republicans have expressed concern about Medicaid funding. Last month, Gov. Bruce Rauner told a reporter he was troubled by federal changes coming to Medicaid. “We’ve got to minimize the hurt to peoples’ lives while we change the system,” he said. But those in Congress still support changes to health care coverage. “I had great concerns about this bill (American Health Care Act). But maintaining the status quo is simply unacceptable,” said U.S. Rep. Randy Hultgren, R-Plano. “Too many are paying monthly premiums higher than their mortgage.”

Competition in health insurance also has diminished. Nationwide, 32 percent of counties have only one insurance provider available through the ACA online marketplace this year, up from seven percent last year, reports the nonpartisan Kaiser Foundation.

About 80 organizations representing a mix of health-care advocates, providers, consumers and workers in Illinois have joined forces in a statewide coalition called Protect Our Care to lobby the Illinois Congressional delegation and inform the public about consequences of proposed changes.

“This is a deeply personal issue to everyone,” Siani said. “It’s hard to talk about because it is so nuanced.”

American perceptions about health care are largely driven by personal experience and partisan views, Keckley said. Quality of care is associated with bedside manner and convenient access to services more than actual outcomes.

Meanwhile, there’s a flaw in the way healthcare is financed and the delivery of care. Insurance companies want to reduce costs, but providers are mostly paid by the volume of patients they see. Also, technological advances play a role in rising costs. Patients expect their providers to have the latest and greatest, when perhaps an older model would perform the same scan or test just as well.

The debate about how health care in America should look doesn’t always include the economics about the way it really works. “We’ve got mass ignorance,” Keckley said, adding health care should be taught in schools. “It’s the fastest-growing line item in the household budget and the fastest-growing at the state and federal level; yet we probably know more about what a loaf of bread costs than what health care costs.”

Globally the United States spends more on health care than any other country in the world, according to a 2015 report by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Countries spending more were likely to have better health outcomes, but that was not the case in the United States. The life expectancy for Americans is lower than the average of countries spending the most on health care.

The United States excels in immediate access to care and the latest and greatest technological advances, says Richard Kaplan, a health-care expert and a law professor at the University of Illinois. “But in terms of the big metrics — how many people are covered, how long do they live, and how much does it cost — we are an outlier,” he says. “A fair number of people are OK with that, but others say we can do better.”

Americans can expect the debate on health care to go on for years to come, Keckley says. By the 2020 election cycle, he thinks the conversation will be about whether the nation should go to single-payer health care. He says Medicare patients are the most satisfied with their insurance coverage and care, while the better-educated, younger population is least happy.

Millennials also view the current system as too complicated. If employers become unable or unwilling to keep up with rising premium costs -- and as millennials become more involved in politics -- there will be more calls to change the system. Keckley says, “Bernie Sanders tapped into something”