Talk Like An Opera Geek attempts to decode the intriguing and intimidating lexicon of the opera house.

After the death in 1848 of Gaetano Donizetti (a virtual composing machine who cranked out over 60 operas in 27 years), one man alone, Giuseppe Verdi, changed the face of Italian opera in the 19th century.

Verdi broke new ground at almost every turn in his career. In such early successes as Ernani, he introduced a vibrant potency to music for lower male voices. In middle period works like Rigoletto and La Traviata, he deepened the richness of individual characters while broadening dramatic complexity. And in Verdi's late operas, he combined a new mastery of vocal expression with swift, taut pacing, turning Otello into a riveting thriller and Falstaff into a virtuosic, sparkling comedy.

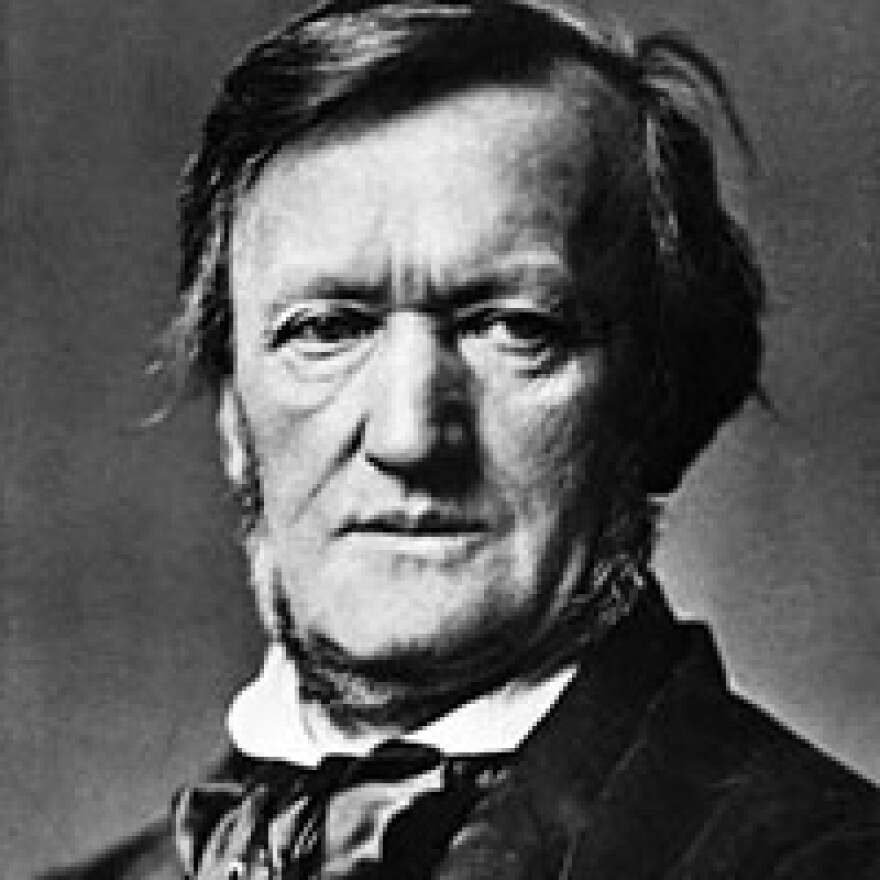

Wagner The Game-Changer

Meanwhile, in Germany, Richard Wagner was turning opera on its head. Described by one observer as a "one man artistic movement," Wagner thought of himself (something he did a lot) as much more than a composer. He became an omnipotent creator who ruled over every aspect his expansive "music dramas," which he thought of as total works of art (Gesamtkunstwerke).

Wagner was unique in that he wrote all of his own librettos and obsessed over minute details of staging. He was the first to darken the house lights during performances, and the first to design a radically new opera house solely for his works. Wagner exploded the length, breadth and height of music theater, changing it forever. His gargantuan operas have inspired composers, authors, directors and even dictators.

Read More And Hear Some Music

The music itself, which can sound both ravishing and unsettling, was the subject of much controversy in its time. Even today, entire books have been written on the single, enigmatic chord that opens his opera Tristan und Isolde. And the intricate lexicon of repeating musical motives matched to the characters and plot devices in the epic 18-hour Ring cycle is another spectacular innovation still studied in depth.

Wagner remains a polarizing figure for his rabid anti-Semitism, freewheeling megalomania and his descendants' ties to Adolph Hitler.

Puccini The Hit-Maker

Born 45 years after both Verdi and Wagner, Giacomo Puccini would become another pillar of the world's opera houses. With sweepingly romantic melodies, his operas were stocked not with royalty and Nordic gods but with common people. He once said that the key to his success was placing "great sorrows in little souls."

Part of that success rests on the shoulders of Pietro Mascagni, who had a massive hit in 1890 with Cavalleria Rusticana, a tunefully melodramatic love story streaked with violence. It ushered in verismo, a style of operatic realism Puccini adopted and refined.

Puccini's most beloved opera, La bohème, deftly balances comedy and tragedy in a detailed score rich with effects, such as a passage at the top of Act 3 for flutes and harp that depicts falling snow. Puccini's orchestrations became more sophisticated with each new opera, culminating in the unfinished 1926 Turandot, with its Chinese melodies (both real and imagined) and modern harmonies.

Although Puccini's operas were occasionally accused of containing shallow music and characters, no Italian since has matched his irresistible tunes, orchestral palette and staying power.

Hear The Music

Giuseppe Verdi: "Rigoletto" (1851)

"Rigoletto, opera [Act II, No. 15c, "Piangi, fanciulla)]"

Verdi thought the title character of Rigoletto (based on Victor Hugo's play Le roi s'amuse) was "a creation worthy of Shakespeare." The hateful, hunchbacked court jester's life is softened only by his unconditional love for his daughter, Gilda. That she eventually dies in Rigoletto's arms as a result of his vengeful mistakes deepens the complexity of the drama and the character. It's a sign of Verdi's greatness that we care for a murderous man with fatherly convictions. In this touching duet with Gilda (soprano Cheryl Studer), Rigoletto (baritone Vladimir Chernov) sings "Weep, my child, let your tears fall upon my breast." Rigoletto's simple phrase, repeated four times, is backed by subtle clarinets, horns and cellos with plucked notes that fall like teardrops. It's a small oasis of compassion that ends as the two voices intertwine in serenity.

Puccini: "Tosca" (1899)

"Tosca, opera [Recondita armonia]"

The severe, almost dissonant opening chords of Tosca herald a sound world far removed from that of Puccini's previous opera La bohème. His harmonies are more aggressive, the music even more seamless, pointing the way toward the advances of Madama Butterfly and Turandot. Still, in Tosca, an opera labeled by one critic a "shabby little shocker," Puccini weaves in his usual arias and duets of delicious intensity. In a stroke of good fortune, his career coincided with the rise of the phonograph. His four-minute arias, filled with thrilling high notes and hummable melodies, helped make him, and singers like Enrico Caruso (who recorded this version of Tosca's "Recondita armonia" in 1909), wealthy superstars.

Wagner: "Tristan Und Isolde" (1859, premiere 1865)

"Tristan und Isolde, opera, WWV 90 [Act 3. Scene 3. Mild und leise wie er lächelt]"

Wagner said he wanted to push himself to the limit musically in Tristan. He succeeded perhaps even beyond his own expectations. The open-ended, searching "Tristan Chord" that begins the opera may be the most discussed sound in music history. Wagner's imaginative expansion of harmonic possibilities has been credited with paving the way for modern music. Fans of Franz Liszt will tell you Wagner stole ideas from him. The planned premiere of Tristan in 1861 was scrapped after 77 rehearsals. Wagner's ravishingly sensual music, depicting an insatiable urge for love, was initially deemed not only unplayable but also perhaps dangerous to the ears. The four-hour story of a mismatched pair of lovers ends with the death of Tristan and some of the sexiest music ever composed in the rapturous "Liebestod" (Love-Death), sung here by Nina Stemme.Below are musical examples from this operatic triumvirate. Have your own favorite arias by Verdi, Wagner and Puccini? Tell us all about them in the comments section.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.